Did You Hear That? A Study into How Brains Perceive Music

Have you ever started to sing along to an obscure song just because someone is whistling that tune? As a composer and musician, senior Seth Metcalfe wondered if there’s something deeper in the brain when it comes to music perception.

“I wanted to do something that intersected both my majors,” said the music and psychology double major. He discussed ideas with Assistant Professor of Psychology Joe Harris, his research advisor, and they explored topics related to perception, identifying a specific class of auditory perceptual illusions — hearing something that isn’t there.

One of Metcalfe’s early inspirations was a paper he wrote for another class about Sergei Rachmaninoff’s famous Piano Concerto No. 2 and how his perception altered over time.

“This is something that the first time I listened to it, I loved it, but every time I’ve listened to it since, it’s been different,” he said.

When he learned the back story about the composer and the piece — Rachmaninoff composed it after a disastrous reception to his first symphony led to a years-long deep depression — his perception of the work changed. “Now, I cannot hear those opening chords without thinking of a funeral bell.”

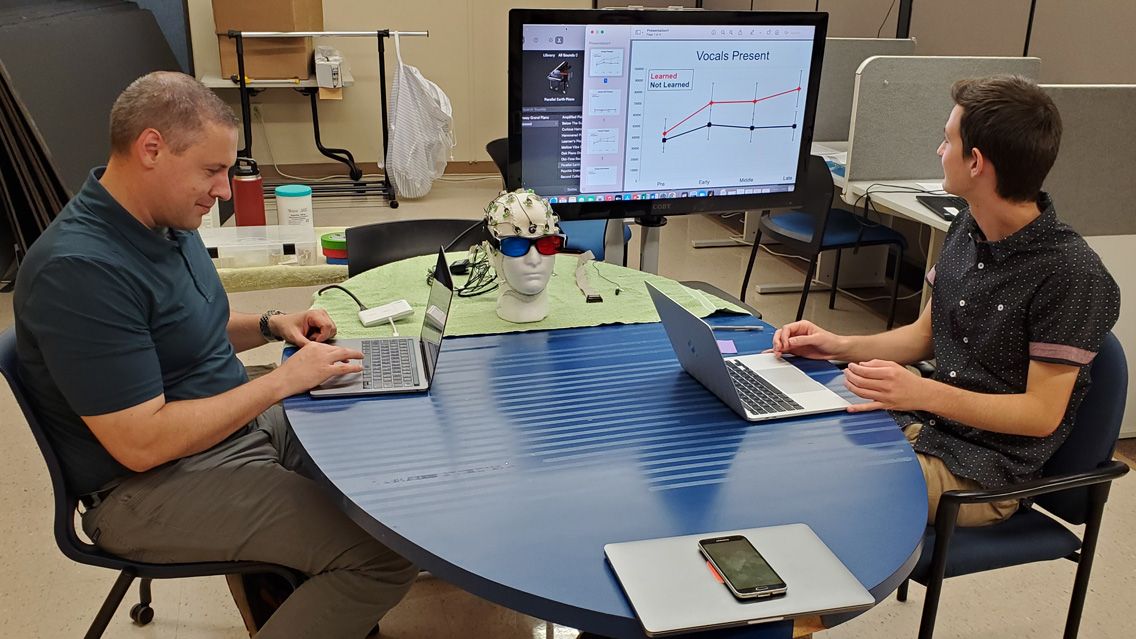

Seeking to learn more about how previous experience and exposure affects music perception, Metcalfe and Harris crafted this innovative project. Their study explores how the brain hears vocals even when they’re not present – illusory perception – and how the brain fills in the missing information akin to blind spot studies done in the visual domain. Through the late summer, the pair have run 14 participants through their study, with the hope of reaching 40 participants in early fall.

They first asked their participants if they could discern vocals from a subset of the song clips, with vocals (and everything else) rendered into a generic digital piano sound by MIDI conversion. They would indicate by pressing and holding a button anytime they heard the non-existent vocals.

Next up, they exposed the participants to the original versions, with vocals, for a partial number of the song clips. Finally, participants listened to the same full set of initial MIDI clips; they repeated this process twice more and all the while Metcalfe recorded changes in the difference in reaction between those songs and the unadulterated versions.

So far, the results are promising. Even with just 10 seconds of exposure to the original song’s vocals, a significant increase in the perception of illusory vocals has emerged for the corresponding MIDI versions. These results support their hypothesis that experience drives the perception of vocals where there are none, with prior knowledge giving the brain the tools it needs to fill the empty spaces.

“In a behavioral task like this, it’s pretty rare to start seeing significant effects this early on,” said Harris. “These results show the learning that takes place when the listener hears the real lyrics is both fast and key to the occurrence of the MIDI vocal illusion. More generally, it supports the notion that our perception is not just a result of simply translating the physical reality of what’s out there, but a constructive process that draws on factors like expectations, context, and experience.”

Harris and Metcalfe believe the additional data they plan to collect through the early fall will confirm their hypothesis even further. Metcalfe will present this study in November at the Illinois State Music Teachers Association conference in November and at the Student Expo in the spring. The pair plan to publish the research in a peer-reviewed journal in the future.

Metcalfe hopes this study will also lead to further interdisciplinary projects between music and psychology.

“I guess what this is speaking to is that you can physically interpret something differently based on your prior knowledge,” he said. A budding composer, he will carry this understanding, and the results of this study, going forward.

“For composing, even if I’m trying to write a piece of absolute music, if there’s something there in my head, whether or not I can communicate it, there is a story (behind it).”

- Mel Huang